Almost 2 years into the existence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, its main mystery remains unsolved. Why do some people contract severe viral pneumonia and die, while others have a very mild or no symptoms at all?

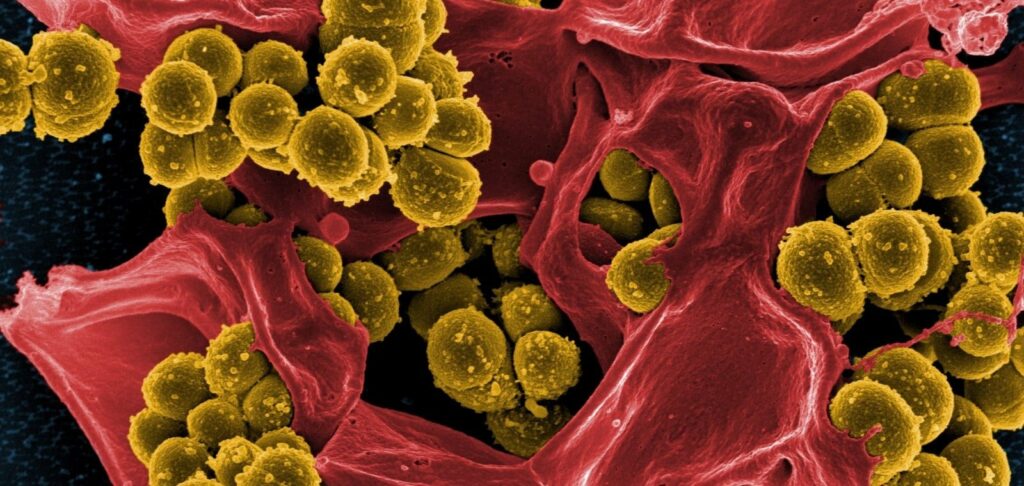

Researchers from the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University (USA) have hypothesized that the severity of disease may be influenced by the microbiome, that is, the bacterial composition of the nasal passage. The nasopharyngeal mucosa acts as a natural barrier to invaders. It also contains an array of immune cells, and their response to respiratory viruses is key. On the other hand, it is abundant with ACE-2 receptors to which the virus binds, that is, it is a “gateway” for the entry of infection.

Previous studies have shown that the nasal microbiota can influence viral load, immune response and symptoms of rhinovirus infection, which is responsible for 10-40% of colds. The same thing, according to scientists may be happening with Covid-19.

The results of their new study confirm that the microbiota of patients with Covid-19 and their immune response to the virus are indeed linked. Distinct patterns emerged when the scientists examined the microbiota of 27 people who tested negative for the virus, 30 who tested positive but had no symptoms, and 27 who tested positive with moderate symptoms that did not require hospitalization.

Researchers found both quantitative and qualitative changes in the microbiota in Covid-19. People with symptoms of the disease had very low numbers of bacteria in the nasopharynx compared to people in the negative group and the positive group without symptoms.

Regarding the qualitative composition of the microbiota, infected individuals had significantly higher levels of two bacterial species:

- Cutibacterium, commonly found on the skin and associated with acne as well as cardiac and postoperative infections.

- Cyanobacteria, which can be found in contaminated water but are a common inhabitant of the microbiome in humans. These bacteria usually enter the body through mucous membranes, such as in the nose, and are known to cause pneumonia and liver damage. Those who were symptomatic had twice as much of this bacteria as their asymptomatic counterparts.

There were no significant changes in microbiota diversity between the asymptomatic and symptomatic patients – just these big differences in volume. For example, their graph of Amylibacter bacterial counts looked like a rung of a ladder when the researchers compared asymptomatic patients to people with symptomatic disease. In contrast, some other bacteria tended to decrease in symptomatic cases.

Thus, a strong association between the bacteria living on the nasopharyngeal mucosa and the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection was evident. However, because the study was observational, the scientists were unable to determine whether the changes in the microbiota caused the Covid-19 symptoms or were a consequence of the infection. In the near future, they intend to find an answer to this question, and to determine whether the microbiota can be a predictor of disease severity, and whether its restoration can be a means of treating the infection.

Shutterstock/FOTODOM UKRAINE photos were used

Ravindra Kolhe, Nikhil Shri Sahajpal, Sagar Vyavahare, Akhilesh S. Dhanani, Satish Adusumilli, Sudha Ananth, Ashis K. Mondal, G. Taylor Patterson, Sandeep Kumar, Amyn M. Rojiani, Carlos M. Isales, Sadanand Fulzele. Alteration in Nasopharyngeal Microbiota Profile in Aged Patients with COVID-19. Diagnostics, 2021; 11 (9): 1622 DOI: 10.3390/diagnostics11091622