What is malaria?

Galen was convinced that malaria was one of the manifestations of fever.

The misconception took root and existed in medicine for more than 15 centuries.

Only in the XVII century this disease was singled out as an independent among other diseases accompanied by fever.

Well, and a full understanding of it scientists made up in the early XX century – it took the development of chemistry, microbiology and physiology.

Today we know that the malaria mosquito, or anopheles, carries the disease.

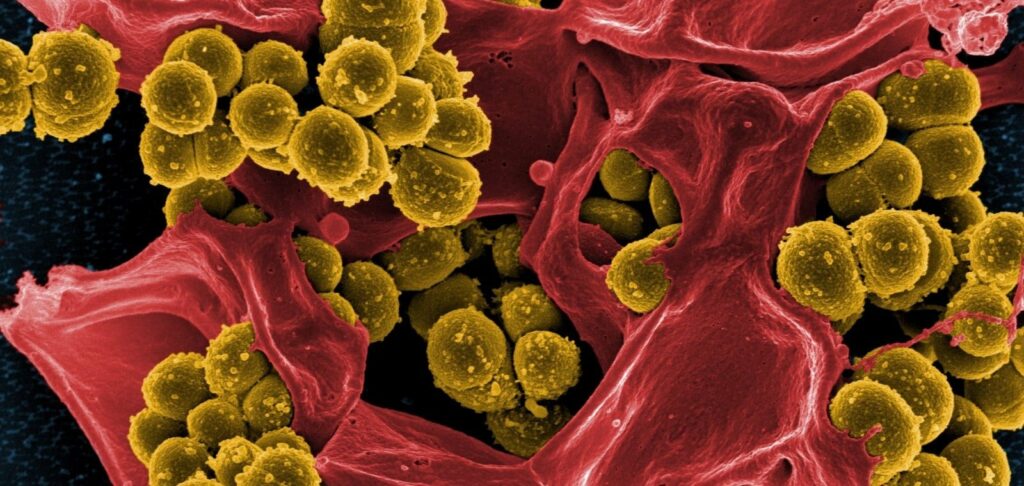

When bitten with its saliva, single-celled organisms – malarial plasmodia in the form of a special form – sporozoites – enter the human bloodstream.

First, they with the bloodstream penetrate into hepatocytes and tissue macrophages, where there is a sexless reproduction of the parasite with the formation of forms that are called merozoites.

In the next step, merozoites exit into the blood, where the erythrocytic cycle of the malaria pathogen occurs.

From each erythrocyte destroyed by microbes, 10-20 merozoites enter the blood, which again penetrate intact erythrocytes, clog blood vessels, enter liver cells, fill and destroy them.

The spleen and kidneys are also affected.

The release of merozoites into the blood occurs every 3-5 days and is accompanied by fever attacks, one of which may be fatal.

Part of merozoites in erythrocytes is transformed into sexual forms of the pathogen – male and female gametocytes.

Their further development is possible only in the stomach of the mosquito, where they get together with the blood of a sick person.

Malaria does not leave a stable immunity, re-infection of a person leads to an even longer and more debilitating disease. Out of a hundred people who fall ill, one dies, and the rest remain carriers of malaria pathogens for a long time.

Four species of plasmodia are known to cause three clinical forms of human malaria:

– Plasmodium vivax – the causative agent of three-day malaria;

– P.malariae, the causative agent of four-day malaria;

– P.falcirarum, the causative agent of tropical malaria;

– P.ovale, the causative agent of ovale-malaria (a type of three-day malaria).

America’s secret treasure

A few decades after Columbus’ great discovery, colonists poured into South America.

They fought brutal wars with Indians, but died not only from arrows and tomahawks – no less terrible enemy was malaria.

And all this time around there were hine trees growing…. The few dedicated Indians jealously guarded the secret of healing.

This went on for more than 100 years, until in 1636 the conquistador Juan Lopez de Correjidor was left to die of fever in a small Indian settlement. One woman took pity on him and, breaking the prohibition, began to drink decoction from the bark of the “cava-huccu” – “fever shiver tree”.

The Spaniard quickly recovered and probably would have forgotten about the medicine, if he had not learned that the wife of the viceroy of Peru, Count Tsinhona, was also dying of malaria.

Determined to help the young beauty, Juan took the kava-hucca bark and traveled to the palace.

The court healers greeted him warily, but decided to try the unknown remedy. To their surprise, the Countess soon recovered.

The failure of the Count of Cinchona

The Count of Cinchona arrived in Madrid in 1640 and brought sacks of healing bark. At the court of the king, he was asked to demonstrate the power of the new medicine.

A decoction of the bark was given to a fever patient, but no miracle occurred. Moreover, the count himself soon fell ill, and the bark was just as useless.

Maybe the doctors had misdiagnosed the disease, or maybe the faithful conquistadors had collected the bark from the wrong trees? No one sought an answer to these questions, and although the second batch of bark fully justified hopes, the Count’s failure was ridiculed at court for a long time.

The deserved fame came to him only 100 years later, when Carl Linnaeus included the tree in the lists of known plants, naming it in honor of the count cinchona apothecary.

True, this name did not catch on, and the “hinny tree” went down in history.

The feat of fraud

Opinions of medics were divided. Some of them considered quinine (powdered bark) almost a panacea, while others, on the contrary, spoke of its uselessness.

For example, the personal physician of the Dutch governor Hafzelius, who recommended treating malaria with bloodletting, wrote that quinine bark was harmful because it did not cure fever, but drove it inside, causing “self-immolation of the intestines”.

While the medics were arguing, Jesuit monks took over the distribution of hina. They succeeded in having the healing properties of the powder recognized by the Catholic Church.

But this only inflamed passions – the adherents of other religious movements began to deny quinine.

Thus, the leader of the English bourgeois revolution, Oliver Cromwell, who belonged to the Anglican Church, died of malaria, flatly refusing the medicine.

Official recognition of china received thanks to the British pharmacist Talbot.

Aware of the powder’s scandalous reputation, he began mixing it with other substances, concealing the true basis of his malaria potion.

The fraudster’s fame quickly reached the palace of Charles II and then traveled beyond Britain.

At the request of Louis XIV Talbot arrived in Paris, where he cured many courtiers.

The French king persuaded the apothecary to reveal the recipe of the miraculous remedy in exchange for 40 thousand louis, a title of nobility and the right to trade the drug throughout the country for 10 years. What was the monarch’s indignation when he realized that he had paid so dearly for a long-known drug! But a bargain is a bargain.

Talbot took full advantage of all the privileges, and the quina was added to the register of remedies by royal decree.

“Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet.

Quinine became more valuable than gold, because the raw materials for its production were only available in Spain and Portugal, and the governments of these countries protected their treasure.

Only in 1865, a hundred years after the appearance of quinine factories, did the Englishman Ledger manage to take the seeds of the plant from Bolivia and spread hina trees on the islands of Java, Kalimantan and Sri Lanka.

Once again, however, financial gain proved more important than human health.

As soon as quinine became plentiful and its price fell, plantations were cut down to make way for more profitable crops.

In addition, it turned out that natural quinine has a number of side effects – it causes deafness, hives, and depresses blood formation.

Not surprisingly, many scientists devoted their lives to finding substitutes for quinine. One of them was the German researcher Paul Ehrlich. He studied the properties of paints that selectively killed microbes. In 1891, the scientist found that methylene blue was destructive to malaria plasmodiae.

However, it turned out that the activity of the dye was too low to cure the disease. Continuing his research, Ehrlich found a substance capable of “bypassing” all the cells of the human body, but finding and killing malaria.

It turned out to be a yellow paint – acrychin, which the researcher himself called a “magic bullet”. Acrychin became a reliable and safe substitute for quinine. Its main disadvantage was only its ability to temporarily color the skin yellow.

In parallel, there was a search for other drugs, and as an analog of acriquin, plasmocide was developed.

It did not kill the plasmodium, but deprived it of the ability to reproduce. It soon became clear that malaria treatment was most effective if acriquin and plasmocide were used simultaneously. This made it possible not only to cure the patient completely, but also to stop the spread of the infection.

Most modern antimalarials are derivatives of aminoquinoline and biguanide.

In the treatment of particularly severe forms and malarial coma, quinine is used, as it was more than three centuries ago, only intravenously.

Malaria in Pre-Revolutionary Russia

Malaria was a significant public health problem in the Russian Empire, particularly in the southern regions, the Caucasus, and Central Asia.

Several factors contributed to the widespread prevalence of the disease:

- Favorable climatic conditions for the breeding of malaria-carrying mosquitoes

- Lack of effective methods to control the vectors

- Poor living conditions and sanitation among the population

- Frequent wars and population movements, facilitating the spread of the infection

In the early 20th century, Russia reported approximately 3.5 million malaria cases annually.

Malaria Hindered Russia’s Conquest of the Caucasus and Central Asia

The disease posed a serious obstacle to the colonization of the Caucasus and Central Asia.

In 1913, a public health officer described malaria as the “chief obstacle to successful colonization of the Caucasus and Turkestan” and “the most important disease of the Russian people”.

The Russian scientist I.I. Pantiukhov, in his 1898 article “On the Influence of Malaria on the Colonization of the Caucasus,” lamented that malaria “reigned over all the fertile valleys and the Caucasus plains” and was a constant “assistant in the fight against foreign attacks”.

He observed that out of 80 families who had settled in the village of Bakhlanovka in the Sukhumi district 20 years earlier, only 7 remained; the others had been decimated by malaria or fled.

Malaria Control Efforts in the Soviet Union

After the October Revolution of 1917, the Soviet government initiated a vigorous campaign against malaria.

The following measures were implemented:

- Establishment of the Central Malaria Commission under the People’s Commissariat of Health of the RSFSR in 1921

- Creation of a network of anti-malaria stations and laboratories

- Large-scale measures to drain swamps and eliminate mosquito breeding sites

- Introduction of quinine for the treatment and prevention of malaria

- Public education and awareness campaigns

Malaria Incidence in the USSR Decreased Significantly

As a result of these efforts, the incidence of malaria in the USSR decreased significantly.

In 1934, around 10 million cases were recorded, but by 1960, the number had dropped to just over 3,000.

|

Year |

Number of Malaria Cases in the USSR |

|

1934 |

10,000,000 |

|

1945 |

3,360,000 |

|

1960 |

3,108 |

Soviet scientists such as E.I. Martsinovsky, P.G. Sergiev, and V.N. Beklemishev played a crucial role in the fight against malaria. They developed new approaches to studying the epidemiology of the disease and methods to combat it.

In 1955, the USSR announced a nationwide malaria eradication program, aiming to eliminate the disease within 5-7 years.

Characteristics of Malaria in the Soviet Union

Malaria in the USSR had several distinct features:

- Predominance of three-day malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax

- Presence of P. vivax strains with long incubation periods (8-10 months) and late relapses after 3-5 years

- Seasonality of the disease with peaks in the spring and summer

- More severe course of malaria in Central Asia and Transcaucasia due to the prevalence of P. falciparum

These factors had to be considered when planning and implementing anti-malaria measures. The USSR also provided assistance to other countries in their fight against malaria, sending experts and supplying drugs to countries such as Afghanistan, Mongolia, and Vietnam.

Semashko Battles Malaria in Volga Region

One interesting story illustrates the challenges faced by the Soviet malaria control program.

In the 1920s, the Bolshevik revolutionary and physician Nikolay Semashko, who served as the People’s Commissar of Public Health, personally led an expedition to the malaria-ridden Volga region.

Semashko and his team traveled by boat, stopping at villages along the river to distribute quinine, drain swamps, and educate the local population about malaria prevention.

Despite the harsh conditions and resistance from some locals who were suspicious of the Soviet authorities, Semashko’s expedition made significant progress in reducing malaria incidence in the region.

The history of malaria in pre-revolutionary Russia and the Soviet Union highlights the disease’s impact on public health, colonization efforts, and socio-economic development.

Malaria Situation in Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan

Malaria in Ukraine

Currently, there is no local transmission of malaria in Ukraine, with all registered cases being imported.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were no reported deaths from malaria in Ukraine in 2020.

However, the risk of transmission resurgence persists due to the presence of vectors and favorable climatic conditions.

In 2020, a fatal case of imported malaria was registered in Kharkiv, involving a man who had returned from Equatorial Guinea.

This incident highlights the importance of maintaining vigilance and ensuring proper diagnosis and treatment of imported malaria cases to prevent re-establishment of local transmission.

Ukraine’s history with malaria dates back to the early 20th century when the disease was endemic in the southern regions of the country, particularly in the Crimean Peninsula and the Dnipro River basin.

During World War II, malaria cases surged due to the disruption of control measures and population displacement. In the post-war period, the country implemented extensive anti-malaria campaigns, including the use of DDT for vector control and the mass distribution of antimalarial drugs.

By the 1960s, malaria was eliminated as a public health problem in Ukraine.

Malaria in Russia

In the first half of the 20th century, malaria was widespread in Russia, especially in the southern regions and Central Asia.

The disease was a significant burden on public health and economic development, with millions of cases reported annually.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Russian scientist E.N. Pavlovsky developed the concept of “landscape epidemiology,” which emphasized the importance of understanding the ecological factors influencing the distribution and transmission of diseases like malaria.

This approach laid the foundation for targeted control measures adapted to local conditions.

Following World War II, the country launched a massive malaria eradication campaign, which included the widespread use of DDT, drainage of mosquito breeding sites, and improved access to antimalarial drugs.

By the 1960s, the incidence of malaria had significantly decreased.

However, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the situation deteriorated due to the weakening of epidemiological surveillance and control systems.

Currently, cases of local transmission of P. vivax are registered in some regions of Russia, mainly imported from neighboring countries.

In recent years, there have been reports of autochthonous malaria cases in the Moscow region, raising concerns about the potential re-establishment of local transmission.

Climate change and increasing global travel have also been identified as factors that could influence the future spread of malaria in Russia.

Malaria in Kazakhstan

The primary malaria vector in Kazakhstan is An. messeae, which is distributed throughout the country. In the southern regions, An. hyrcanus and An. claviger are also present.

After gaining independence, the incidence of malaria in Kazakhstan increased, but due to concerted efforts to combat the disease, only sporadic cases, mainly imported, have been registered in recent years. The risk of infection for travelers is considered low.

Kazakhstan’s experience with malaria eradication in the 20th century was marked by the implementation of the Soviet malaria control strategy, which relied heavily on vector control and mass drug administration.

However, the country faced challenges in maintaining the progress achieved during the Soviet era, particularly in the 1990s, when economic and political instability hindered malaria control efforts.

In recent years, Kazakhstan has strengthened its malaria surveillance and response system, focusing on preventing the re-establishment of local transmission.

The country has also collaborated with international organizations, such as the WHO and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, to improve its capacity to detect and respond to malaria cases.

Malaria in Uzbekistan

In the past, malaria was one of the most prevalent diseases in Uzbekistan, with hundreds of thousands of cases reported annually.

After extensive anti-malaria measures during the Soviet period, malaria transmission was interrupted in 1961.

However, in the 1990s, local transmission resumed due to the importation of cases from neighboring countries.

Uzbekistan’s success in eliminating malaria is a testament to the country’s commitment and the effectiveness of its national malaria control program. The program focused on strengthening surveillance, improving case management, and implementing targeted vector control measures.

The country also benefited from the support of international organizations and partnerships, such as the WHO’s Global Malaria Programme and the Roll Back Malaria initiative.

In 2018, Uzbekistan was certified by the WHO as a malaria-free country.

The last local cases of P. vivax were registered between 2010 and 2014.

To prevent the re-establishment of local transmission, Uzbekistan maintains a robust surveillance system and continues to invest in malaria control and elimination efforts.

One of the key lessons learned from Uzbekistan’s experience is the importance of cross-border collaboration in malaria elimination.

The country has actively engaged with its neighbors, particularly Tajikistan and Afghanistan, to coordinate malaria control efforts and prevent the importation of cases. This regional approach has been crucial in achieving and sustaining malaria elimination in Uzbekistan.

We Must Always Be Vigilant Against Malaria

While significant progress has been made in the fight against malaria in Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan, the threat of transmission resurgence persists due to the presence of vectors, favorable climatic conditions, and the risk of importation from endemic countries.

Sustained efforts in epidemiological surveillance, prevention, and preparedness to respond to potential outbreaks are essential.

The experiences and lessons learned from these countries can inform global efforts to eliminate malaria and highlight the importance of regional cooperation and adaptation of control strategies to local contexts.