This pain is not “imaginary,” is not merely psychosomatic, and does not mean that the person is “fine.” Understanding the mechanisms of functional pain helps explain why symptoms persist, avoid unnecessary tests, prevent unwarranted treatments, and reduce chronic anxiety.

Why it hurts even if tests show nothing

In everyday understanding, pain is always a consequence of damage: inflammation, injury, degenerative changes, or infection. However, in clinical practice, situations are increasingly common where pain exists, but no objective changes are found.

A person may experience pain in the back, abdomen, head, or muscles for years, undergo numerous tests — and each time hear: “Everything is normal.”

This is not a rare anomaly, but a distinct group of conditions well-known in medicine, although it often remains unclear to patients.

Why pain does not always indicate a serious disease

What functional disorders are and why they do not show up on tests

Functional disorders are conditions in which an organ or system works improperly, but structural damage is not detected.

The organ exists, tissue is preserved, but regulation is impaired.

Typical examples:

-

abdominal pain without inflammation or ulcers;

-

back pain without herniation or nerve compression;

-

headache without vascular or space-occupying changes.

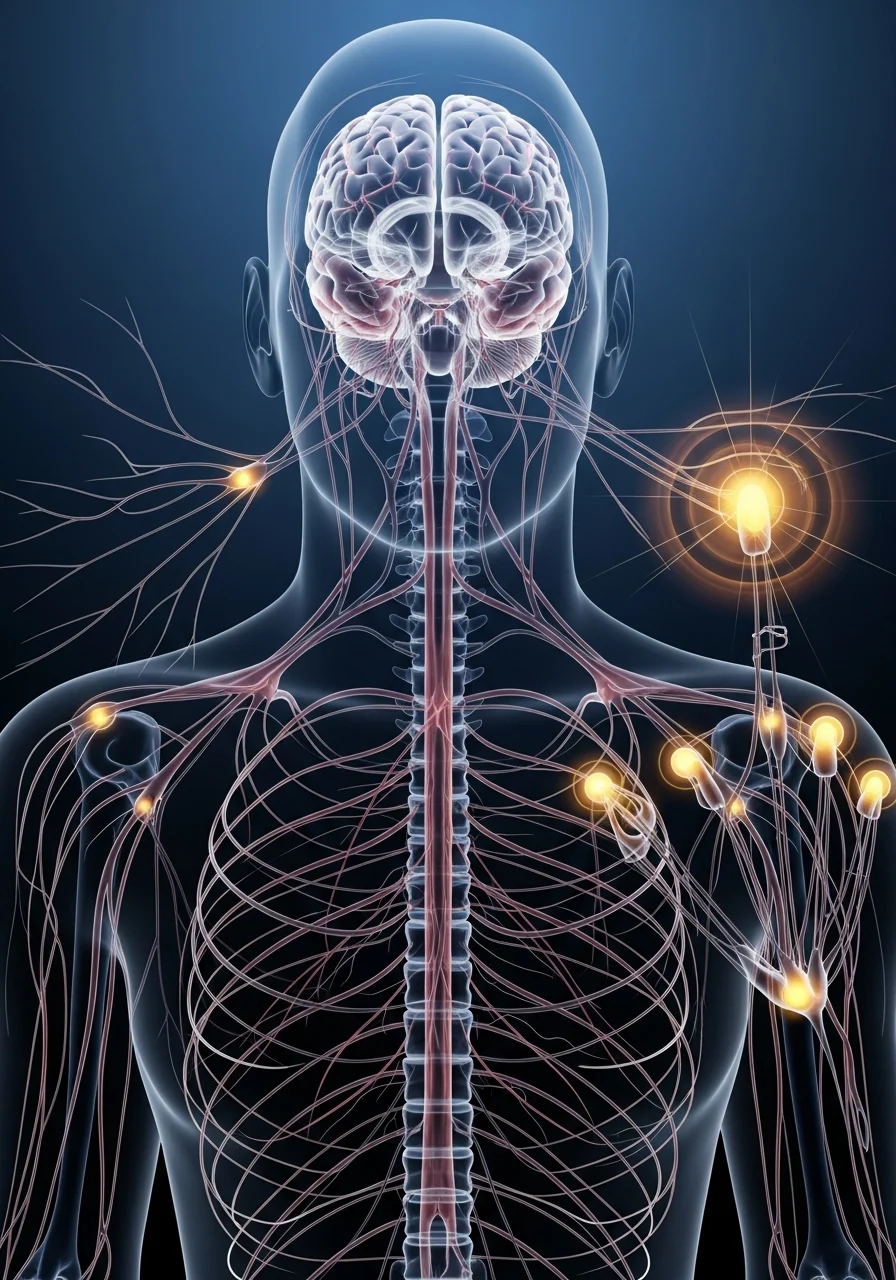

How the nervous system generates the sensation of pain

Pain is not a direct signal from tissue to the brain. It is the result of complex information processing by the nervous system.

When this system becomes hypersensitive, it can:

-

amplify normal signals;

-

respond to harmless stimuli as threats;

-

maintain pain even after the original factor disappears.

How functional pain differs from structural pain

Table 1. Functional vs. structural pain

| Feature | Functional Pain | Structural Pain |

|---|---|---|

| Changes on MRI / Ultrasound | Absent | Detected |

| Connection with stress | Often pronounced | Less pronounced |

| Symptom variability | High | Usually stable |

| Response to load | Unpredictable | Predictable |

| Effect of painkillers | Unstable | More clear |

Functional pain does not mean exaggeration or simulation. It means that the source of the problem lies in regulation, not in an anatomical “breakdown.”

Why MRI, ultrasound, and tests may appear normal even if it hurts

Most instrumental methods detect structural changes but cannot assess:

-

disruption of nerve signal transmission;

-

pain pathway sensitization;

-

functional spasms;

-

failures of adaptive mechanisms.

Therefore, the absence of findings does not mean the absence of a problem.

How tension and stress maintain pain in the body

Stress is rarely the sole cause of pain, but it:

-

lowers the pain threshold;

-

disrupts muscle and vascular regulation;

-

maintains a state of chronic tension.

This is a physiological process, not a “psychological invention.”

When functional pain becomes chronic

Table 2. Factors contributing to chronic pain

| Factor | How it acts |

|---|---|

| Constant anxiety | Increases focus on symptoms |

| Self-treatment | Masks pain without addressing the mechanism |

| Lack of explanation | Creates fear and distrust in the body |

| Overload | Maintains nervous system sensitization |

| Lack of recovery | Prevents the system from “restarting” |

There is no single main cause among these factors — pain is maintained systemically, which is why it seems so persistent.

Questions and answers about pain without a cause

Can functional pain be real if tests are normal?

Yes. The reality of pain is not determined by test results.

Does the absence of a diagnosis mean the problem is “in the head”?

No. Functional disorders are bodily regulatory mechanisms, not imagination.

Are functional pains dangerous?

They rarely threaten life but can significantly reduce quality of life.

When does pain require additional attention?

If the pain worsens, occurs at night, is accompanied by neurological symptoms, weight loss, or fever.

Conclusions

Pain without an obvious cause is not a dead end or a fiction. It is a signal of disrupted interaction between the body and the nervous system. Recognizing the functional nature of pain reduces fear, helps avoid aggressive treatments, and creates conditions for recovery.

References

-

Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for pain diagnosis and treatment. Pain, 2011.

-

Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia and related conditions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 2014.

-

NICE Guidelines: Chronic pain (primary and secondary).

-

IASP Terminology and Pain Classification.

-

PubMed: review articles on functional pain syndromes.