Microplastics are no longer just an environmental issue — today they are a factor that directly affects human health. Studies show that an average person may ingest between 0.3 and 5 g of microplastics per week — the equivalent of a “credit card.”

Particles are found in water, seafood, fruits, vegetables, salt, tea, coffee, and even in the air.

The question is simple: how do these particles behave in our bodies, and what can be done to minimize the risks?

Sources of Microplastics: Where They Enter Food and Water

Main Pathways of Exposure

-

Drinking water. Microplastics are detected in a significant proportion of bottled water samples; they are also found in tap water.

-

Seafood. Fish, mollusks, and shrimp accumulate particles in their digestive systems.

-

Fruits and vegetables. Plants can absorb nanoparticles through soil and water.

-

Salt and spices. Especially sea salt, which concentrates pollution from the oceans.

-

Tea bags. Some of them release billions of nanoparticles during brewing.

-

Packaging and plastic tableware. Heating and long-term storage accelerate particle migration into food.

How Microplastics Act Inside the Body

Possible Mechanisms of Impact

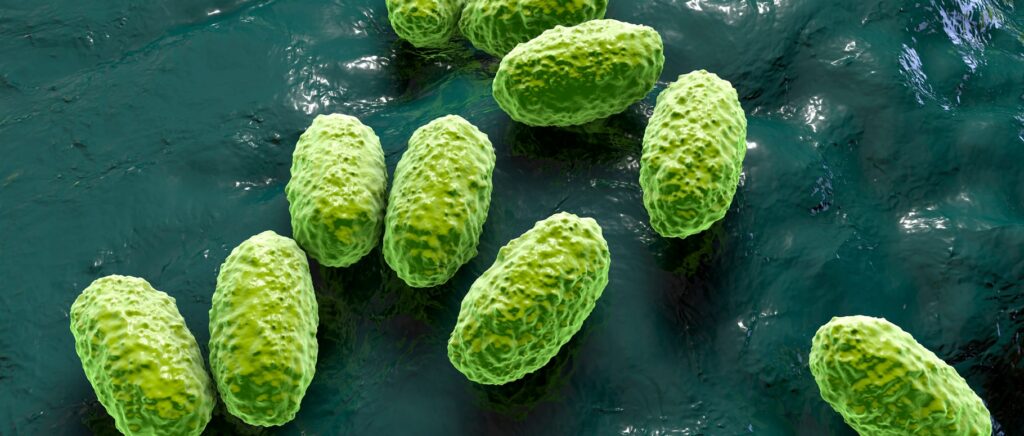

The mechanism of action depends on the size of the particles:

-

Microplastics (1–1000 μm) generally do not penetrate deeply and are partially excreted, but may damage the mucosal lining.

-

Nanoplastics (<1 μm) can penetrate cell membranes, circulate via blood and lymph, and potentially reach the liver, spleen, and brain.

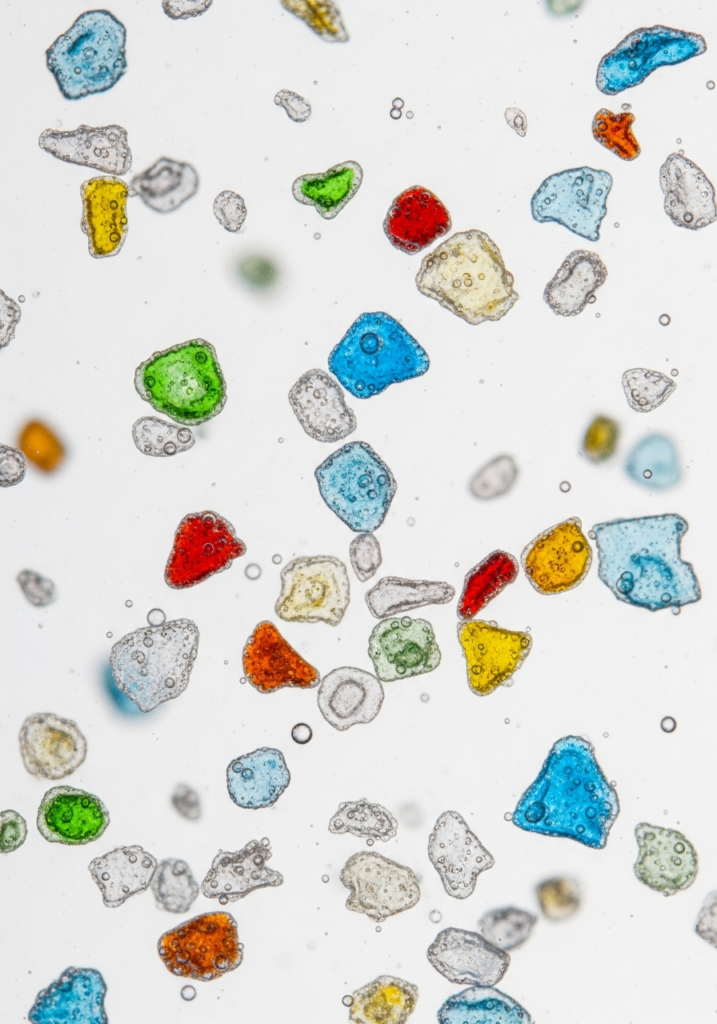

Impact on the Digestive System

-

Disruption of the gut microbiome. Particles alter bacterial balance, reducing beneficial strains and promoting dysbiosis.

-

Local inflammation. Microplastics can irritate the intestinal walls, increasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

-

Impaired barrier function. Evidence suggests that nanoparticles may increase intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”).

-

Effects on enzymatic activity. Certain polymers and associated additives may reduce the activity of digestive enzymes.

Systemic Effects

-

Oxidative stress. Increased free radical production and depletion of antioxidant defenses.

-

Chronic low-grade inflammation. A risk factor for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

-

Hormonal disruptions. Plastic components (BPA, phthalates) act as endocrine disruptors.

-

Cardiometabolic risks. Potential associations with insulin resistance and altered lipid profiles.

-

Effects on the reproductive system. Some studies indicate possible impacts on fertility and fetal development.

Main Types of Microplastics and Their Potential Effects

Table 1. Types of plastics, sources, and potential health effects

| Type of plastic | Where it is most commonly found | Potential impact on the body |

|---|---|---|

| PET (polyethylene terephthalate) | Water and beverage bottles, packaging | Oxidative stress, possible microbiome changes, migration of monomers and additives |

| PP (polypropylene) | Disposable cups, containers | Local irritation, potential impact on intestinal barrier integrity |

| PS (polystyrene) | Tableware, food packaging, foam products | Toxic monomers (styrene), endocrine disruption |

| PVC (polyvinyl chloride) | Pipelines, packaging, plastic wrap | Phthalates → hormonal disruption, effects on the liver and endocrine system |

| PE (polyethylene) | Plastic bags, food wrap | Disrupted lipid metabolism, chronic low-grade inflammation |

How to Reduce Microplastic Exposure in Everyday Life

Practical Habits That Actually Work

-

Replacing plastic in contact with food.

Glass, metal, and ceramic instead of plastic containers and bottles. -

Avoid heating food in plastic.

Do not reheat food in plastic containers in the microwave. -

Water filtration.

Reverse osmosis or multi-stage filters show the highest efficiency in removing particles. -

Less disposable tableware.

Especially for hot drinks and meals. -

Packaging.

Choose products packaged in glass, paper, or biodegradable materials whenever possible. -

Tea and coffee.

Prefer loose-leaf tea and a French press over plastic tea bags and capsules that release particles when heated.

The Role of Nutraceuticals: Can Supplements Protect the Body?

No nutraceutical “flushes” plastic out of the body. However, nutrients can help reduce harm from:

-

-

oxidative stress,

-

chronic inflammation,

-

microbiome disruption,

-

increased burden on the liver and detoxification systems.

-

Key Groups of Nutrients

-

Antioxidants.

Vitamin C, vitamin E, polyphenols (green tea, grapes, berries), resveratrol, and astaxanthin help neutralize free radicals. -

Omega-3 fatty acids.

They reduce inflammatory processes, support the cardiovascular system, and may decrease systemic inflammation associated with chronic toxin exposure. You can purchase high-quality Omega-3 supplements on the website medizine.ua in the Omega-3 section. -

Probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics.

Restoration of the microbiome, strengthening of the intestinal barrier, and reduction of local inflammation. We wrote about the main types of postbiotics and how they work in the article “Postbiotics of the New Generation: Metabolites, Signaling Peptides, and Short-Chain Fatty Acids”. -

Dietary fiber.

Soluble and insoluble fiber (inulin, FOS, resistant starch) support regular peristalsis and nourish beneficial bacteria. -

Support of detoxification systems.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC), glycine, sulfur-containing amino acids, and glutathione support detoxification phases in the liver. -

Chlorella, spirulina.

There is a hypothesis that they may bind certain toxins; it is important to use only certified products free from their own contamination with heavy metals.

Nutraceuticals and Their Possible Role in Microplastic Exposure

Table 2. Potential nutraceutical support tools

| Nutrient / supplement | Mechanism of action | Who may benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Probiotics / postbiotics | Restoration of the microbiome, strengthening of the intestinal barrier, reduction of local inflammation | People with bloating, dysbiosis, irritable bowel syndrome |

| Omega-3 (EPA/DHA) | Anti-inflammatory effects, support of cell membranes and the cardiovascular system | Residents of large cities, people with metabolic syndrome, chronic stress |

| Vitamin C + polyphenols | Powerful antioxidant protection, neutralization of free radicals | Those living in conditions of high air and water pollution |

| NAC, glutathione | Support of the antioxidant system and liver detoxification | Patients with increased liver load, urban residents with high stress levels |

| Dietary fiber (inulin, FOS) | Normalization of intestinal transit, nourishment of beneficial bacteria | People with a low-fiber diet, a tendency toward constipation |

What Modern Science Says: A Brief Overview of Key Studies

-

Animal studies show that nanoplastics can penetrate epithelial barriers and induce inflammatory responses in the intestines and other organs.

-

Publications in leading journals report changes in microbiota composition under the influence of microplastics: both diversity and the proportion of beneficial bacteria decrease.

-

Some studies associate exposure to microplastics with markers of metabolic syndrome (insulin resistance, dyslipidemia).

-

There is evidence of endocrine disruptions caused by plasticizers and additives that migrate from plastics, especially when heated.

-

Studies of water purification systems show that reverse osmosis filters can remove up to 90–99% of microplastic particles.

(Specific DOI/PMID references can be added in the publication according to the selected journal format.)

Conclusion

Microplastics are no longer a futuristic threat but a reality of the modern lifestyle. They are present in water, food, and air, penetrate the digestive system, affect the microbiome and barrier functions, and potentially influence hormonal and metabolic status.

It is impossible to completely avoid microplastics, but it is possible to significantly reduce the burden:

-

by changing cookware and packaging,

-

by improving the quality of drinking water,

-

by supporting the microbiome, antioxidant, and detoxification systems through diet and nutraceuticals.

This is not a “one-week detox” but a long-term strategy that works for the future—less systemic inflammation, a better metabolic profile, and lower risks of chronic diseases.

References

-

Leslie HA et al. Human consumption of microplastics. Environment International.

-

Lu L et al. Uptake and accumulation of microplastics in the gut microbiota. Environment International.

-

Yong CQY et al. Toxicity of microplastics and nanoplastics in mammalian systems. Science of The Total Environment.

-

Wang J et al. Microplastics as contaminants in the food chain. Journal of Hazardous Materials.

-

Kosuth M et al. Synthetic polymer contamination in bottled water. Frontiers in Chemistry.